Spectrum Simulator

| Spectrum Simulator | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Voting | - | |

| Developer | David Tindale | |

| Company | Whitby Computers | |

| Release | 1985 | |

| Platform | C64 | |

| Genre | Development | |

| Media | ||

| Language | ||

The Spectrum Simulator enables the C64 to run ZX Spectrum BASIC programs. It was published on cassette (DM 49.50) in 1985 by Whitby Computers, UK.

Background[edit | edit source]

Christmas 1983 saw the start of the home computer boom, and sales were dominated by two machines: The Commodore 64 and the ZX Spectrum. And the big question was, which computer was the best?

This was the first ever generation of kids to own a computer, and nobody really knew much about them. That didn't stop them declaring their machine to be superior. Both camps had a lot of fun boasting about their own hardware and hurling insults at the other. Mostly, these comments were along the lines of, 'You should buy a real computer!' (C64'ers) versus 'I bet you wish you had all our cheap games!' (ZX'ers).

But, in retrospect, which was the best?

In the sound and vision arena, the C64 was obviously massively superior. It sported 3-channel synthesizer sound and arcade-quality sprite graphics. It was a true arcade machine. In comparison, the only sound the humble Spectrum could manage was a doleful one-bit beep, and it suffered from a slow display that offered little in the way of graphical capabilities. In sound and graphics, the C64 won hands down, no contest.

But surprisingly, the little ZX, the poor man's computer, with its blue rubber keyboard and tiny inbuilt speaker, held its ground and even won a few victories. It thrived thanks to the army of obsessed assembler maniacs who formed around it and who went on to produce some of the most memorable games of the era. And with such a multitude of cheap-as-chips titles available, no Speccy fan would ever turncoat and swap his beloved ZX for a C64. No way. When you factored in these elusive subjective points, neither machine could be declared the outright winner of the title Best Home Computer—though that didn't stop both sides declaring victory.

Eventually, the C64 vs. Spectrum wars fizzled out. And by New Year, 1984, peace had returned to the playground. Or rather, the arguments had turned from home computers to focus on that year's important new trends: Walkmans, break-dancing, leg warmers, and mullet haircuts.

But for the next couple of years, the die-hard computer fanatics (who by that time had graduated from playing games to programming BASIC) continued to quietly but cheerfully poke fun at other people's computers and to sound off about the superiority of their own and why they would never join the other side. Then in 1985, a strange software title appeared on the market that would help bring these geeky Montagues and Capulets closer together. The Spectrum Simulator.

As the original programmer explained: "There was a complete annotated disassembly of the Spectrum ROM available as a book, and I recoded it all pretty much byte-for-byte from Z80 to 6510. This meant even a couple of the Spectrum bugs remained in the emulation. The code was bigger in the 6510, due to its less powerful instruction set, and it was often hard to find enough machine registers to use, since the Z80 had more of those."

Features[edit | edit source]

Thanks to this straight machine code transliteration, the C64 was able to closely mimic the ZX Spectrum. The running simulator even looked like the original Sinclair, with its 32 characters-per-line display of black text on a white background. Graphics and sound commands were fully functional, rendering the ubiquitous Commodore POKE commands redundant, and this made programming easier compared to CBM BASIC V2.0. Surprisingly, original ZX Spectrum tapes would load directly into the C64. And the Spectrum Simulator could even control the Commodore-Floppy 1541. It treated the 1541 / IEC double drive as a Microdrive tape. Theoretically, up to 4 Microdrive double drives could be emulated.

However, like the original Spectrum hardware, the simulator only had one simple, unmodulated audio channel available. Sounds was limited to simple beeps, and therefore extensive sound programming with the Spectrum Simulator was impossible.

And despite its impressive technical feat and near-perfect compatibility, the resulting simulator wasn't completely accessible. The software's 20-page English instructions only explained the BASIC dialect in broad terms. Users who wanted to do any serious ZX programming had to first get their hands on a copy of an authentic Sinclair manual.

And ZX BASIC had its quirks. It checked each line of input directly after entry, and any errors were highlighted in the form of a blinking question mark at the error position, which irritatingly demanded immediate attention.

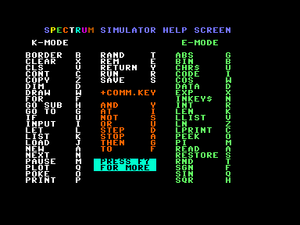

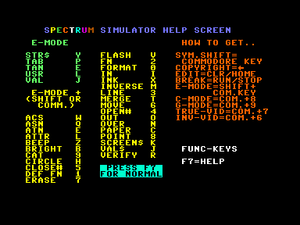

Worse, on the ZX Spectrum, BASIC commands were not entered by typing individual characters but through keywords. For example, pressing the 'P' key resulted not in the usual letter-P appearing on the screen, as with any normal computer, but with the appearance of the BASIC keyword PRINT. The original intention of this scheme was to save typing—Sinclair owners had to type on a cheap rubber keyboard (known in England as 'dead flesh'), and though it was an improvement over the ZX81's keyless membrane, it was still unbearably slow, and anything that saved typing on dead flesh was welcome. But ironically, instead of making typing easier and faster, the ZX's keywording scheme made it harder and slower. Irritated Speccy users had to keep looking up which key was assigned to which keyword. Tricky combinations of Shift and Control were needed. This strange arrangement, as well as making Spectrum owners bash the keyboard in frustration, must have utterly baffled C64 owners, who didn't even have the benefit of having the keywords printed on the keys. However, the F7 key had a neat integrated help menu (see the image at the side of this page), which explained all the key assignments.

BASIC Commands[edit | edit source]

The following BASIC commands are included in the Spectrum Simulator:

BEEP, BORDER, BRIGHT, CAT, CIRCLE, CLEAR, CLOSE#, CLS, CONTINUE, COPY, DATA, DEF FN, DELETE, DIM, DRAW, ERASE, FLASH, FOR TO, FOR TO STEP, FORMAT, GO SUB, GO TO, IF THEN, INK, INPUT, INVERSE, LET, LIST, LLIST, LOAD, LOAD DATA, LOAD CODE, LOAD SCREEN$, LPRINT, MERGE, MOVE, NEW, NEXT, OPEN#, OUT, OVER, PAPER, PAUSE, PLOT, POKE, PRINT, RANDOMIZE, READ, REM, RESTORE, RETURN, RUN, SAVE, SAVE LINE, SAVE DATA, SAVE CODE, SAVE SCREEN$, STOP, VERIFY

Bugs[edit | edit source]

INK 9 and PAPER 9 commands both cause a crash.

Limitations[edit | edit source]

Due to hardware differences, including the MOS 6510 CPU instead of Zilog Z80 and the different memory organization of both computers, it was not possible to simulate machine language code, except for POKEing system variables. Furthermore, the program itself required some storage space, so that only about 30 KB of free memory was available for BASIC programming.

Although the complete command set of the ZX Spectrum was implemented, the BRIGHT command, which defines two color brightness levels, was not applicable to the C64 hardware and therefore didn't function.

So, the Spectrum Simulator was in no way a full hardware emulator. Rather, it merely provided an alternative BASIC dialect. Avid programmers got an extra insight into the possibilities of BASIC programming. To people who grew up in that era, this needs no explanation: BASIC was the go-to language of the time, and many magazines published self-type listings. They were an economical way to get your hands on software and to learn your trade.

And in fairness, the Sinclair Simulator never intended to completely emulate the ZX Spectrum. Its sole purpose was to allow ZX BASIC to run on the C64, and it hit its mark. Yes, it was a solution in search of a problem. Nevertheless, it was one of the many brilliantly pointless science-for-science's-sake curios that appeared back then, whose cumulative side effect was to train and inspire a whole new generation of computer programmers. Today, those same programmers have Linux vs. Windows to argue about. Plus ca change.

Literature[edit | edit source]

- Happy Computer Heft 6/85 S.140 "Wolf im Schafspelz"

- Artikel "Wolf im Schafspelz" in stcarchiv.de